Before we start, I have one word for you: SPOILERS.

There. Let’s begin.

Every screenwriter, aspiring or otherwise, knows the immense surge of inspiration that can come after watching a great film. It’s jet fuel. It propels us to keep working, to keep striving to make our own storytelling measure up. A great piece of filmmaking can be a better lesson than the most acclaimed college course on the planet. Which leads me to Breaking Bad.

Breaking Bad isn’t just television. It’s filmmaking of the highest possible caliber. For screenwriters, it’s a goldmine (or money-stuffed barrel) of lessons on great storytelling. Though, if you’re only paying attention to the finished product, you might get a whole set of lessons that are, well, frankly… wrong.

I’m not gonna lie, I’m a little worried that right now, somewhere, screenwriters and Hollywood execs are shouting “Make it darker!” Or perhaps, “Give it more ‘holy crap’ moments!”

Yes, Breaking Bad is a very successful series (though it’s important to remember that it wasn’t for the majority of its life on the air). Yes, Breaking Bad is dark. Yes, Breaking Bad is chalk full of “holy crap” moments. But that’s not why it’s good.

What makes it good, at least in this humble writer’s opinion, is the absolute honesty with which Vince Gilligan and his writing staff treat their characters and the world they inhabit.

The Breaking Bad writers don’t shove those “holy crap” moments into the middle of the story just to get a rise out of the audience. They carefully earn every one. A guy opening his door and getting shot is dramatic, absolutely. But when the character who opens his door is Gale — perhaps as innocent as a meth-cook can be — and the character who shoots him is Jesse — someone totally aversive to murder – the drama is a hundred fold.

Drama that good only lies at the end of a long road. One covered with too much coffee, tears and heads banged against keyboard. But there’s really good drama at the end!

The first step on said road is to ask: “Where is the character’s head at?” It’s something the Breaking Bad writers refer to constantly as the starting point for their discussions. What does each character want at that very moment? What do they fear? What are they willing to do to get what they want? Just as importantly, what are they NOT willing to do?

When these questions are answered, a character is formed. Then, telling the story becomes a matter of asking: “What would this character do in this situation?” If you’re honest, you get good drama. Breaking Bad writers often talk about having great ideas for scenes or story beats that would fall by the wayside, simply because that’s not where the characters wanted to go.

A favorite example of mine is Drew Sharp, the boy on the motorbike whom Todd shoots dead. About halfway through “breaking” (meaning, plotting out the story beat by beat) the first eight episodes of Season 5, the writers had a general idea for where the series was going. The plan was for Walt to retire and Jesse to take over as Albuquerque’s new kingpin. Then Todd shot Drew Sharp.

From that moment on, everything changed. The writers knew there was just no way Jesse would let that slide. There was just no way he would stay in the meth business. So he quit. The writers didn’t lock themselves into their original plan, they let the characters lead the way.

I was curious if Todd was a character created out of necessity – aka, someone to shoot Drew Sharp – so I asked Breaking Bad writer and producer Thomas Schnauz. The answer was no: Todd came first, and Drew Sharp was a pretty last minute addition. Who knows what the writers’ original plan for Todd was, but it just goes to show their willingness to throw away their plans and let the story come naturally.

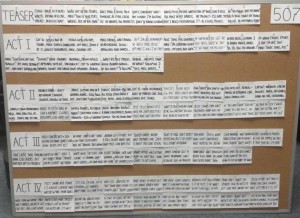

Famous amongst fans of the Breaking Bad writers are the index card filled cork boards. When breaking each episode, the writers would work together to plan out every single beat of the story in extensive detail. They would write out beats on 3×5 index cards and pin them to a cork board. All together, an episode would average somewhere around 60-65 cards. That’s a lot of plot, and a lot of detail. But it ensures that every episode has a rock solid structure, then, when an individual writer goes off to work on an episode’s script, they get to “do a little jazz”, as writer Peter Gould puts it.

Each writer creates the dialogue, embellishes the scenes and puts their unique stamp on their individual episodes. They get to do this with confidence, because they know most of the heavy lifting has already been done by the group. But the work and time put into that heavy lifting cannot be ignored. Especially when the writers write themselves into a corner, something which, let’s be honest, they tend to do with frequency.

Midway through Season 3, Walt and Jesse are trapped in the RV with Hank looming outside like a hungry shark. It’s a moment that pins the audience to the edge of their couches and makes them wonder “Just how are Walt and Jesse going to get out of this?”

Well, believe it or not, the writers had to ask themselves the same thing.

They often reference this moment as an example of just how painful the writing process can be. It took hours upon hours of thinking, of talking and coming up with plenty of bad ideas until a Breaking Bad worthy solution was thought up: A fake phone call to Hank telling him something horrible had happened to Marie.

Made for some damn good drama, didn’t it?

I came upon a similar roadblock recently while working on a screenplay. Well into the climactic scene, my protagonist was ready to unleash her master plan and defeat the bad guy. Ta-da! The sun shines high and everyone cheers. Feel good film of the year. Then something dawned on me (I like to call it logic), and I realized that there was no way the bad guy wouldn’t anticipate the protagonist’s plan. So he did, and he turned it on its head.

And I had no idea what she was going to do.

At that point, I wanted to shut my laptop off, go get lunch and convince myself the solution would come easier after some heavy procrastination. Then I remembered Hank outside the RV, and I realized that if I didn’t have any clue how the protagonist was going to get out of her plight, chances are the audience wouldn’t either.

So I kept working. There was a lot of staring at the screen, a lot of start and stop writing, and so much thinking I ought to have paid tuition. The bad ideas came first. And man, oh, man, was there a lot of them. But finally, after what felt like three days in the desert, I came up with a solution. The scene – and as a result, the screenplay – is ten times better because of it.

What allowed me to make it better is the inspiration I’ve derived from the Breaking Bad writers. The lessons countless hours of watching the show and closely analyzing it have taught me. Chief amongst which is: HONESTY.

There’s an index card with “Where’s Walt’s head at?” taped on the wall next to my desk. It’s a constant reminder to always stay true to my characters. I must look at the thing a thousand times a day, and every time, it fills me with inspiration and an immediate self awareness if what I’m currently working on isn’t treating the characters with honesty.

So, next time you’re writing a script and you feel the biting urge to make it darker, just because Breaking Bad is dark AND good, stop. Take your hands off the keyboard, put the pencil down (yes, I know there’s at least one of you still left) and remind yourself that Breaking Bad isn’t good because it’s dark. It’s good because it’s honest.

—–

PS: For anyone interested in studying the craft behind Breaking Bad further, I cannot recommend the “Breaking Bad Insider Podcast” more highly. Hosted by Kelley Dixon, one of the show’s editors, and Vince Gilligan himself, the podcast discusses every episode from Season 2 till the finale in glorious, extensive detail. Guests such as other writers, directors, cast and crew members are always present, and the amount of insight one can get about the making of the show is simply unmatched. Do yourself a favor and start listening.

Also, most of the Breaking Bad writers are on Twitter. In particular, Thomas Schnauz and Moira Walley-Beckett are quite active and will often take the time to answer questions. As is the writers’ assistant, Gordon Smith, who provides a different view of the process.